Beyond the Cherry Trees: The Life and Times of Eliza Scidmore

By Jennifer Pocock, former assistant researcher at National Geographic Traveler magazine.

The peak cherry tree bloom has already come and gone, carpeting the sidewalks of America’s capital city with a layer of pink and white petals. For the Japanese, this blossoming is a metaphor for life: a brief and brilliant burst, followed by a certain fall.

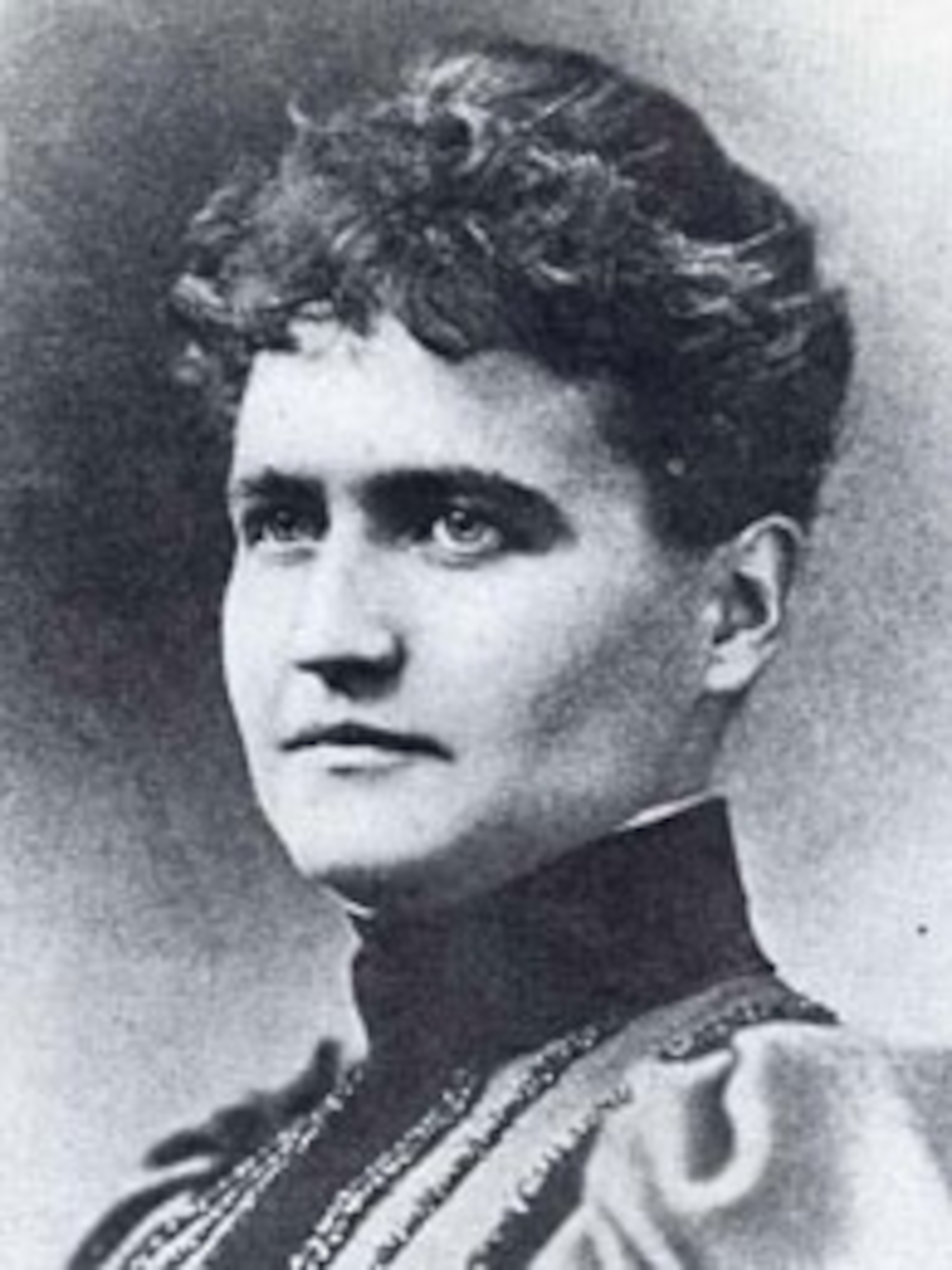

Yet the life of Eliza Scidmore — the woman who brought the now-famous trees to Washington a hundred years ago today — seems a testament to the contrary. Scidmore (pronounced Sid-more) labored for 24 years to bring the government around to the idea of the planting. And on March 27, 1912, she finally helped root the saplings in a small unassuming ceremony at the north end of the Potomac Basin.

Scidmore was both steadfast and intrepid. Born into a family of adventurers, she had been bitten by the travel bug early in life and did whatever she could to continue seeing new, far-flung places, despite the criticism she must have met for her independent spirit.

She attended Oberlin College for a short time before leaving to write society columns for newspapers around the country. The money she earned from the job allowed her to explore other, more exotic travel possibilities. The first of these was a journey to what was then “the Department of Alaska” — and the start of a lingering love affair with the Last Frontier — in 1883.

“Each summer I bought my long purple ticket, reading from Portland to Sitka and return, with pleasurable anticipations; and all of them – and more — being realized I yielded up the last coupons with regret,” she wrote.

One of the steamships she took to Alaska, the Idaho, became the first to successfully navigate the northern end of Glacier Bay. James Carroll, the ship’s captain, named Scidmore Island after his esteemed passenger.

These trips provided fodder for articles, which were published by many of the top newspapers and magazines of the day, and then collected and republished as a book in 1885. It was considered the first comprehensive travelogue of Alaska, recording, with near-anthropological scope and precision, not only her travels, but also descriptions of the towns and customs of its people.

Her adventures continued. In 1885, she visited the Far East for the first time on a trip to Japan to visit her brother. She fell in love with the people, the culture, and most of all, the cherry blossoms. Soon after her return, she began to petition Washington to plant the delicate trees in the barren areas around the Capitol — a fight that would last almost a quarter of a century.

Scidmore joined the National Geographic Society in 1890, two years after it was established, where she became not only the Society’s first female writer, photographer, and board member, but also an associate editor and overseas ambassador.

She was behind other firsts, as well, having brought the word tsunami to the English lexicon through her coverage (for National Geographic) of the aftereffects of an earthquake off the coast of Hondo in the summer of 1896.

Though she worked tirelessly in Washington, D.C. for the Society and for her cherry trees, Scidmore’s restless spirit always called her to far-off places. India, China, Java, and the Philippines, to name a few.

In Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), she climbed Dambool Rock, something she described in a 1907 article for National Geographic magazine as “an enchanted mesa that burned blood red and purple in the sunset and seemed impossible of attainment by any two-footed climber.”

But through all of her adventures, her heart belonged to Japan — and to her beloved blossoms. Her dogged quest to see a “Mukojima on the Potomac” paid off when First Lady Helen Taft finally got wind of her proposal and provided enough political clout to get the idea off the ground, or, rather, in it.

Scidmore returned to Japan again and again, leaving the U.S. for good in 1923 when the government began clamping down on travel. Her firsthand accounts and hand-colored photographs of the landscape and people there brought a new understanding of Japanese culture to a curious America in the lead up to the first World War. When she died in 1928, her ashes were buried in Yokohama, under a springtime carpet of pink and white petals.

For someone so out there in the world, Scidmore was a fiercely private individual. Having instructed her parents to burn her personal letters upon her death, we have little insight into who she was behind closed doors. But Scidmore leaves behind seven books of travel writing, 17 photo-driven articles in National Geographic magazine, and thousands of blooming cherry trees along the Potomac that continue — despite the odds — to provide a fitting legacy for her abiding spirit.

This article was written with some consultation with Paul Martin, a former National Geographic Traveler editor. His new book, Secret Heroes: Everyday Americans Who Shaped Our World, is available for pre-order on Amazon.com.

Related Topics

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- How to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beachesHow to see Mexico's Baja California beyond the beaches

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?